Conversations About the End of Time and The National Gallery of Art – Part 1: Time Scales and the Year 2000 - Stephen Jay Gould

Sunday, April 30, 2017 at 01:40AM

Sunday, April 30, 2017 at 01:40AM What follows is a kind of dual journal entry that features excerpts from the book Conversations About the End of Time and photographs of paintings on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. The non-fiction book format is discussion-based, and consists of interviews with four renowned scientists, theologians, philosophers, and writers: Stephen Jay Gould, Jean-Claude Carriere, Jean Delumeau, and Umberto Eco. I’ve only transcribed a fraction of the material available in the book, which is as enlightening and timely read in a day-in-age of naysayers and pessimists who seem adamant to adopt Malthusian perspectives about the future of humanity and are resigned to the prospect that humans are doomed so we may as well commit collective suicide to put ourselves out of our common misery and facilitate the healing of the planet. This book offers glimmers of hope, although not necessarily for us. This first part, titled Time Scales and the Year 2000, features excerpts from an interview with biologist-paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould (1941 – 2002), who taught at Harvard and worked at the American Museum of Natural History. (To see Part 2 of this series, which features excerpts from an interview between the editors of the aforementioned book and French thelogian Jean Delumeau, click here.)

Do you think humanity has reached an advanced state in its evolution?

That’s a question we can’t answer. We have no idea what we are capable of on the basis of our genetic make-up. After all, we haven’t been around very long, the human race is very young, about 200,000 years only. From the cultural point of view we are scarcely more than 5,000 years old. Language and technology are only just beginning, the most surprising , terrifying, exciting things can still happen, we haven’t yet begun to explore the possibilities of social and technological organization. Most scenarios, it’s true, are probably more terrifying than inspirational. But what of it? Perhaps you’ve noticed: we’re not very good at making predictions! On the other hand, we are very good at forecasting catastrophes for the wrong time.

Does humanity need great moments of crisis in order to progress?

Perhaps it doesn’t really. We’ve succeeded in surviving so far! But I have noticed that we only decide to do something when we’re forced to it. We only begin to find solutions to famine when lots of people have died of hunger, we wait for genocide to be committed before denouncing it, we take steps against overpopulation when there is a threat of famine…Why? I don’t know. It’s probably just a deep=rooted tendency in each of us. It’s difficult to change, and changing sooner is even more improbable than transforming one’s own self. The people in power want to stay there, and that desire is a powerful factor in creating inertia. It’s often necessary to attack the powers as they might be… I’m always surprised that there aren’t more automobile accidents, given how many irresponsible people there are driving. A catastrophe is really quite a rare event.

You seem almost optimistic.

Let’s just say that I tend to be prudently optimistic. I don’t predict that things are going to get better, but at least I have the certainty that we have the means of putting up a fight. That’s probably the best we can hope for.

We talked about the arbitrary nature of the calendar, but aren’t geological eras just as arbitrary?

No Way! That’s just what is so remarkable about the scales of geological time – the fact that they’re not arbitrary. When the geological scale was established in the nineteenth century, the boundaries were placed between eras which corresponded to mass extinctions. Not because scientists had a theory about the decimations, but because, empirically, the major causes in the fossil archives coincide with the time when they took place...

In my laboratory at Harvard University there are drawers full of the fossils of animals that lived before the great extinction at the end of the Permian age. They’re very easy to recognize. Once you’ve seen them, you can never again confuse them with the fossil of organisms that lived after that extinction. In fact the destruction was so radical at that particular moment that the form of what we find later is totally different. You only need to open those drawers the once to understand that these boundaries are not arbitrary; there are the great rifts in evolution. The last great boundary is between the Cretaceous and the Tertiary, and bears the trace of the impact from some huge, extra-terrestrial object. We know that the fall of this asteroid caused the extinction of the dinosaurs. And in the end, the reason why we’re sitting here talking like this is that an asteroid struck the earth, wiped out the dinosaurs, and spared a few little mammals. Darwin thought that the mass extinctions were human inventions resulting from the incompleteness of fossil archives. Today we know that they were real enough: the history of life has been punctuated by several massive and brutal decimations… Take, for example the mass extinction at the end of the Ordovician, 438 million years ago; or the one at the end of the Devonian, 367 million years ago. But the worst was at the end of the Permian, 250 million years ago. It wiped out, at one go, almost 95 per cent of all invertebrate marine species. Finally, we have the extinction of the dinosaurs, on the boundary between the Cretaceous and the Tertiary, 65 million years ago, trigged by the impact of an extra-terrestrial object containing iridium.

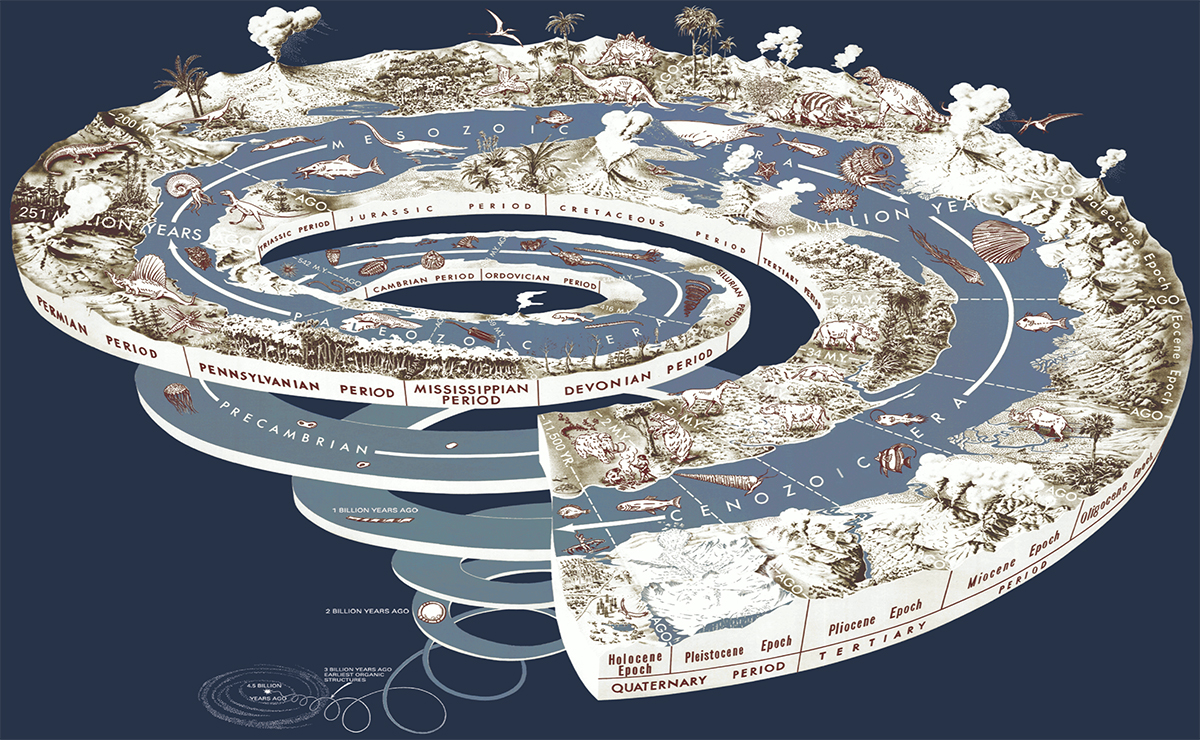

Image: Geologic Time Spiral - A Path to the Past (USGS)

Image: Geologic Time Spiral - A Path to the Past (USGS)

What did people say back then, whenever they found a fossil?

In Antiquity they believed that fossils were the remains of antediluvian animals or human beings, the remains even of mythological heroes like Antaeus, Polyhemus, or the giants mentioned in the first chapter of Genesis. In 413, in City of God, Saint Augustine tells of a gigantic molar, the size of a hundred human teeth, that was found not far from Carthage and put on display in a church: ‘These ancient bones,’ he writes, ‘show clearly, all these centuries later, how large primitive bodes were.’ For a long time people thought human beings had become smaller in the course of history, it was a commonly held opinion among ancient writers. In the seventeenth century collectors made much of the giant shoulder blades and teeth displayed in their cabinets of curiosities. Yet as early as the end of the fifteenth century Leonardo da Vinci was saddened to see these crazy notions still current, and he declared himself convinced of the organic origin of fossils.

In any case, it takes more than just finding one isolated fossil in order to conceive of mass extinctions. A fossil is simply the trace of a particular animal’s stay on earth. You need prior knowledge in order to understand that they represent periods in the history of the living. Up until the nineteenth century nobody had such knowledge. The first dinosaur bones were found in 1825. No one knew of their existence.

You’ve written that ‘extinction is the normal fate awaiting all species.’ Basically, survival is the exception, and disappearance the norm.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that extinction is a solution to the dangers currently threatening us. People who don’t want to face up to the reality of the situation sometimes tend to use the discoveries of paleontology to say: everything’s going to disappear anyway, so what does it matter, why worry about the ecosystem? They even end up becoming advocates of the worst-case scenario; since new species have developed after every mass extinction, why not wish for a new extinction that will be even more productive? It’s a quite unjustified line or argument, because it’s irrelevant to the scale of human life… The earth itself isn’t in any danger. It’s already experienced great explosions that were much more powerful than anything all our bombs are capable of producing. And it recovered from them, even if it did take millions of years to do so… What is a millennium? For a geologist it’s the twinkling of an eye, but in human experience it’s a gigantic, almost in conveyable length of time. When the year 2000 comes, there’ll be very few people alive who were around at the turn of the last century. No one on this earth was alive in 1800…

There have been only five mass extinctions after all. You know, we’re very lucky that no mass extinction every wiped out life altogether... At the end of the Permian we came very close to total destruction, about 95 per cent of species.

What I mean is that we should not worry about what’s going to happen to our planet. We should not be big-headed about it, we’ve poisoned it but it will survive.

What are your thoughts about the hole in the ozone layer and the greenhouse effect?

Everything depends on what we do in the future. This brings us back to our discussion about time-scales. I am prepared to believe that the greenhouse effect poses no major danger to the planet itself, at least not the greenhouse effects that we are capable of causing. It will warm the planet up to temperatures that it has already experienced several times in the past. So it isn’t a danger to the planet, but it is a danger to us. If the poles begin to melt, our towns and cities will be flooded, our lives will be severely disrupted. But the earth itself will simply have slight bigger oceans, that’s all.

That happened at the time of the single continent, the so-called Pangaea.

It’s happened several times. Once can’t extrapolate from the present curve, for the following reasons: if the level of carbon monoxide increases alarmingly and there’s further global warming, we’ll take steps to bring it under control. We’d even be able to reverse the trend. Everything depends on human will, on our intelligence, on our capacity to co-operate, on our politicians. The dangers are real, the anxieties ligitmate. Some people think the present trend is bound to continue and will lead to disaster. But in fact there’s nothing inevitable about it, and we can even hope that we’ll be smart enough to reverse it.

Reader Comments