I approached another skeleton, this one too afraid to talk, turning away after whispering a single word, “Dachau.”

-Love Thy Neighbor, A Story of War, About the war in former Yugoslavia, Peter Maass, 1996

This was but a prelude; where books are burnt, human beings will be burnt in the end.

-German poet Heinrich Heine, 1820

For the liberation of a people more is needed than economic policy, more than industry: if a people is to become free, it needs pride and willpower, defiance, hate, hate and once again hate!

-Adolf Hitler, Munich speech, April 10, 1923

Haven’t you heard the fatwas that have filled our streets and mosques by permitting people to eat cats, dogs and other animals that have already been killed by the bomb attacks? Are you waiting for us to eat the flesh of our martyrs and our dead after fearing our lives?

-Syrian Imam pleading for help after the lifting of religious bans on eating dogs, 2013

Man’s Search for Meaning is a powerful pocketbook which examines how it is possible for a person to find purpose in life when the surrounding world has fallen apart and one becomes a concentration camp prisoner during the Nazi Holocaust. The author, Viktor E. Frankl (1905 – 1997), was Austrian psychiatrist working as the head of neurology at the Rothschild Hospital (the only Jewish hospital) in Vienna during the start of WWII. After the National Socialist government shut down the hospital, the American consulate offered Frankl a U.S immigration visa, which would have allowed him to leave. He declined the offer for the sake of his aging parents, and in 1942 he and his family were arrested and deported. Viktor Frankl spent the next three years of his life in four different extermination camps. “The odds of surviving the camp were no more than one in twenty-eight, as can easily be verified by exact statistics,” writes Frankl.

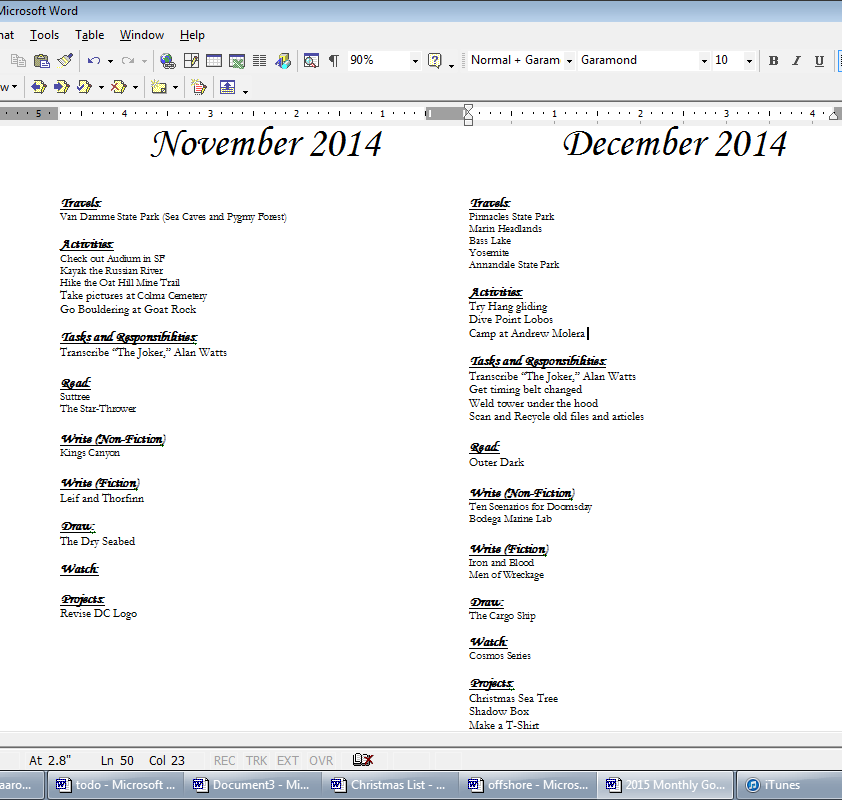

Below you will find important excerpts I have transcribed from the book, a slideshow of the afterward to the book (which is good to read to obtain an overview of Dr. Frankl’s life), a slideshow of scanned excerpts from the book (which I would highly encourage you to read in full), and then a slideshow of a separate book that my father purchased for my brother and me on a visit to Dachau in the mid-1990s. The book is called, Concentration Camp Dachau, 1933 – 1945, and was published in 1978 by the International Dachau Committee. The introduction states:

This catalogue is intended to accompany the visitor to the Dachau Memorial Museum… Although Dachau was not intended as a “mass extermination camp,” hunger and illness, arbitrary killings and mass executions along with the SS doctors’ pseudo-scientific experiments, resulted in the continual “extermination” of prisoners… Originally planned to accommodate 5,000 prisoners, the camp was primarily intended to eliminate all political opposition. In the course of time, in addition to Jews, gypsies and anti-Nazi clergymen, any citizens who made themselves unpopular with the regime were imprisoned here… On April 29, 1945, the liberators of the Dachau camp found more than 30,000 survivors of 31 different nationalities in the disastrously overcrowded barracks, and as many again the subsidiary camps attached to Dachau. During its 12 year of existences, 206,000 prisoners were registered in Dachau. The number of “non-registered” arrivals can no longer be ascertained. During this period of time 31, 951 deaths were registered. However, the total number of deaths in Dachau, including the victims of individual and mass executions and the final death marches will never be known.

Man's Search for Meaning, Afterward (right-click to view image in full):

Excerpts from Man’s Search for Meaning

As I have already mentioned, the process of selecting Capos was a negative one; only the most brutal of the prisoners were chosen for this job (although there were some happy exceptions). But apart from the selection of Capos which was undertaken by the SS, there was a sort of self-selecting process going on the whole time among all of the prisoners. On the average, only those prisoners could keep alive who, after years of trekking from camp to camp, had lost all scruples in their fight for existence; they were prepared to use every means, honest and otherwise, even brutal force, theft, and betrayal of their friends, in order to save themselves. We who have come back, by the aid of many lucky chances or miracles – whatever one may choose to call them – we know: the best of us did not return. (Pg. 5)

The significance of the finger game was explained to us in the evening. It was the first selection, the first verdict made on our existence or non-existence. For the great majority of our transport, about 90 percent, it meant death. Their sentence was carried out within the next few hours. Those who were sent to the left were marched from the station straight to the crematorium. This building, as I was told by someone who worked there, had the word “bath” written over its doors in several European languages. On entering, each prisoner was handed a piece of soap, and then – but mercifully I do not need to describe the events which followed. My accounts of have been written about this horror.

We who were saved, the minority of our transport, found out the truth in the evening. I inquired from prisoners who had been there for some time where my colleague and friend P---- had been sent.

“Was he sent to the left side?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“then you can see him there,” I was told.

“Where?” A hand pointed to the chimney a few hundred yards off, which was sending a colum of flame up into the grey sky of Poland. It dissolved into a sinister cloud of smoke.

“That’s where your friend is, floating up to Heaven,” was the answer. But I still did not understand until the truth was explained to me in plain words. (Pgs. 12 – 13)

Strangely enough, a blow which does not even find its mark can, under certain circumstances, hurt more than one that finds its mark. Once I was standing on a railway track in a snowstorm. In spite of the weather our party had to keep on working. I worked quite hard at mending the track with gravel, since that was the only way to keep warm. For only one moment I paused to get my breath and to lean on my shovel. Unfortunately the guard turned around just then and thought I was loafing. The pain he caused me was not from any insults or blows. That guard did not think it worth his while to say anything, nor even a swear word, to the ragged, emaciated figure standing before him, which probably reminded him only vaguely of a human form. Instead, he playfully picked up a stone and threw it at me. That, to me, seemed the way to attract the attention of a beast, to call a domestic animal back to its job, a creature with which you have so little in common that you do not even punish it. (Pg. 24)

I shall never forget how I was roused one night by the groans of a fellow prisoner, who threw himself about in his sleep, obviously having a horrible nightmare. Since I had always been especially sorry for people who suffered from fearful dreams of deliria, I wanted to wake the poor man. Suddenly I drew back the hand which was ready to shake him, frightened at the thing I was about to do. At that moment I became intensely conscious of the fact that no dream, no matter how horrible, could be as bad as the reality of the camp which surrounded us, and to which I was about to recall him. (Pg. 29)

In spite of all the enforced physical and mental primitiveness of the life in a concentration camp, it was possible to spiritual life to deepen. Sensitive people who were used to a rich intellectual life may have suffered much pain (they were often of a delicate constitution), but the damage to their inner selves was less. They were able to retreat from their terrible surroundings to a life of inner riches and spiritual freedom. Only in this way can one explain the apparent paradox that some prisoners of a less hardy make-up often seemed to survive camp life better than did those of a robust nature. (Pg. 36)

In other work parties the foremen maintained an apparently local tradition of dealing out numerous blows, which made us talk of the relative luck of not being under their command, or perhaps of being under it only temporarily. If an air raid alarm had not interrupted us after two house (during which time the foreman had worked on me especially), making it necessary to regroup the workers after, I think that I would have returned to camp on one of the sledges which carried those who had died or were dying from exhaustion. No one can understand the relief that the siren can bring in such a situation; not even a boxer who has heard the bell signifying the finish of a round and who is thus saved at the last minute from the danger of a knock out. (Pg. 46)

Those who had pitied me remained in a camp where famine was to rage even more fiercely than in our new camp. They tried to save themselves but they only sealed their own fates. Months later, after liberation, I met a friend from the old camp. He related to me how he, as camp policeman, had searched for a piece of human flesh that was missing from a pile of corpses. He confiscated it from a pot in which he found it cooking. Cannibalism had broken out. I had left just in time. (Pg. 56)

And so the last day in camp passed in anticipation of freedom. But we had rejoiced too early. The Red Cross delegate had assured us that an agreement had been signed, and that the camp must not be evacuated. But that night the SS arrived with trucks and brought an order to clear the camp. The last remaining prisoners were to be taken to a central camp, from which they would be sent to Switzerland within forty-eight hours – to be exchanged for some prisoners of war. We scarcely recognized the SS. They were so friendly, trying to persuade us to get in the trucks without fear, telling us that we should be grateful for our good luck. (Pgs. 60 – 61)

Many weeks later we found out that even in those last hours fate had toyed with us few remaining prisoners. We found out just how uncertain human decisions are, especially in matters of life and death. I was confronted with photographs which had been taken in a small camp not far from ours. Our friends who had thought they were travelling to freedom that night had been taken in the trucks to this camp, and there they were locked in the huts and burned to death. Their partially charred bodies were recognizable on the photograph. I thought again of Death in Teheran. (Pg. 62).

An active life serves the purpose of giving man the opportunity to realize values in creative work, while a passive life of enjoyment affords him the opportunity to obtain fulfillment in experiencing beauty, art, or nature. But there is also purpose in that life which is almost barren of both creation and enjoyment and which admits of but one possibility of high moral behavior: namely, in man’s attitude to his existence, an existence restricted by external forces. A creative life and a life of enjoyment are banned to him. But not only creativeness and enjoyment are meaningful. If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an ineradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death human life cannot be complete. (Pg. 67)

The prisoner who had lost faith in the future – his future – was doomed. With his loss of belief in the future, he also lost his spiritual hold; he let himself decline and became subject to mental and physical decay. Usually this happened quite suddenly, in the form of a crisis, the symptoms of which were familiar to the experienced camp inmate. We all feared this moment – not for ourselves, which would have been pointless, but for our friends. Usually it began with the prisoner refusing one morning to get dressed and wash or go out on the parade grounds. No entreaties, no blows, no threats had any effect. He just lay there, hardly moving. If this crisis was brought about by an illness, he refused to be taken to the sickbay or to do anything to help himself. He simply gave up. (Pg. 74)

Once an individual’s search for a meaning is successful, it not only renders him happy but also gives him the capability to cope with suffering. And what happens if one’s groping for a meaning has been in vain? This may well result in a fatal condition. Let us recall, for instance, what sometimes happened in extreme conditions such as prisoner-of-war camps or concentration camps. In the first, as I was told by American soldiers, a behavior pattern crystallized to which they referred as “give-up-it is.” In the concentration camps, this behavior was paralleled by those who one morning, at five, refused to get up and go to work and instead stayed in the hut, on the straw wet with urine and feces. Nothing – neither warnings nor threats – could induce them to change their minds. And then something typical occurred: they took out a cigarette from deep down in a pocket where they had hidden it and started smoking. At that moment we knew that for the next forty-eight hours or so we would watch them dying. Meaning orientation had subsided, and consequently the seeking of immediate pleasure had taken over. (Pg. 139)

It is apparent that the mere knowledge that a man was either a camp guard or a prisoner tells us almost nothing. Human kindness can be found in all groups, even those which as a whole it would be easy to condemn. The boundaries between groups overlapped and we must not try to simplify matters by saying that these men were angels and those were devils. Certainly, it was a considerable achievement for a guard or foreman to be kind to the prisoners in spite of all the camp’s influences, and, on the other hand, the baseness of a prisoner who treated his own companions badly was exceptionally contemptible. Obviously the prisoners found the lack of character in such men especially upsetting, while they were profoundly moved by the smallest kindness received from any of the guards. I remember how one day a foreman secretly gave me a piece of bread which I knew he must have saved from his breakfast ration. It was far more than the small piece of bread which moved me to tears at that time. It was the human “something” which h this man also gave to me – the word and look which accompanied the gift.

From all this we may learn that there are two races of men in this world, but only these two – the “race” of the decent man and the “race” of the indecent man. Both are found everywhere; they penetrate into all groups of society. No group consists entirely of decent or indecent people. In this sense, no group is of “pure race” – and therefore one occasionally found a decent fellow among the camp guards.

Life in a concentration camp tore open the human soul and exposed its depths. It is surprising that in those depths we again found only human qualities which in their very nature were a mixture of good and evil? The rift dividing good from evil, which goes through all human beings, reaches into the lowest depths and becomes apparent even on the bottom of the abyss which is laid open by the concentration camp. (Pgs. 86 – 87)

Man's Search for Meaning (right-click to view image in full):

Concentration Camp Dachau (right-click to view image in full):

Viktor E. Frankl

Thursday, December 1, 2016 at 01:47PM

Thursday, December 1, 2016 at 01:47PM