Spring Migrations in West Sonoma County

Saturday, March 30, 2019 at 03:12AM

Saturday, March 30, 2019 at 03:12AM If you drive from Sebastopol along the Bodega Highway, through the Russian River Valley, you’ll traverse green hills and pastures where dairy cows crop the grass and an occasional cat picks its way across a field. Oak and palm trees line the road westward past apple orchards and vineyards, countryside homes and cafes, fruit and vegetable stands, barns and nurseries, taverns and inns and bygone brothels. A man who sells smoked salmon from the trunk of his car may have set up his hand-painted sandwich board sign featuring a salmon smoking a pipe. The road opens up as you pass the small town of Freestone where smoke from the bakery there can be seen traveling up from the chimney against a backdrop of douglas fir and redwood tree forests which rise north toward Occidental. Past these old stone and logging towns through which the North Pacific Coast Railroad ran over a century ago is the hamlet of Valley Ford where an elderly couple sell homemade beef jerky at the general store. Winter rainfall has drenched the land, bringing forth new plant growth and resurrecting dormant mosses and lichens which thrive and fluoresce in the trees. Toadstools carpet the forest floors where pink calypso orchids bloom, birds hunt exposed worms in creek beds while raptors watch from treetop or telephone pole perches and vultures wheel slowly through the sky. In the higher elevations to the east the ridges of the Mayacamas Mountain Range are dusted in snow and the peak of Mount Helena is snowcapped. The entire area stirs with life after the seasonal rains, which have extinguished the forest fires and bring the rivers to flood, seemingly heralding the hemispherical beginning of yet another planetary orbit around the Sun and another annual chance in our limited lifetimes to experience, explore, and revere the world around us, as well as to strive to heal that which we have damaged. When the leviathan storm clouds disperse rainbows appear by the dozens, cats can be seen flying through the sky, spiders climb up water spouts, and cruising down the wet country road is the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile.

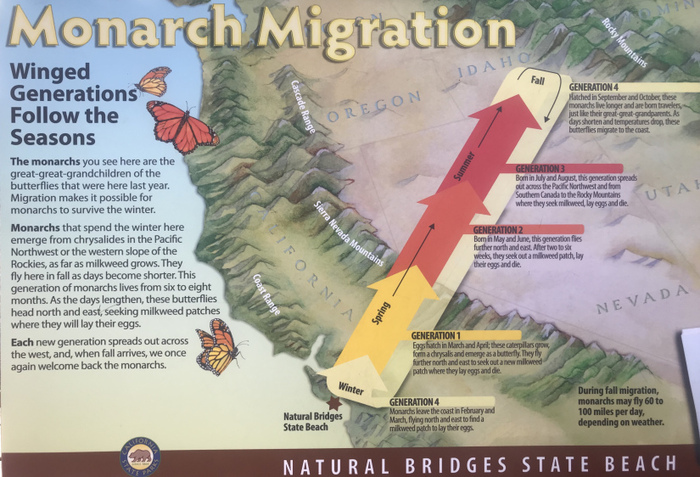

Continuing west toward the coast you’ll past the little town of Bodega, with its fire department, church, saloon, and graveyard all located within a stone’s throw of one another. Bodega Highway ends where Highway One begins, and if you travel north past the eucalyptus groves, windswept cypress trees, and sand dunes you’ll arrive in Bodega Bay, where crab and fishing boats crowd the marina and foghorns toll at regular intervals. The coast is home to billions of intertidal creatures and plants which are the resilient members of animal phylum and plant divisions whose age of speciation span multiple geological epochs. North of Bodega Bay lies the coastal prairies, and had you come here during the late-Pleistocene epoch 1.8 million to ten-thousand years ago, you would have seen pre-historic megafauna such as giant armadillos, ground sloths, woolly mammoths, and bison herds roaming the grasslands. Today you will mainly find humans hiking along the coast or watching for any grey whales migrating offshore. In the winter, as the water turns to ice in polar seas, the grey whales swim six-thousand miles from the arctic to breeding and calving lagoons in Baja California. They return north in the spring, some mother whales with little calves in tow, to return to their summer feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. In the late-spring salmon will perform the return phase of their epic migration which is more mind-boggling than that of the whales: having spent their entire adult lives at sea the salmon will somehow swim back home, finding the very rivers of their birth to spawn and then die. Not to be outdone, monarch butterflies are engaged in an equally astonishing multi-generational migration, with the first generation leaving the cooling Rocky Mountains in the fall and fly to the same coastal hatcheries as their great-great-grandparents to overwinter. In the spring they will begin their journey home, but their entire migrating generation will lay their eggs and die en route, as will then next one, and the next one, until the fourth generation finally arrives at the Rockies having never been there before, only to fly to California in the fall as their forbearers before them have done.

The days grow noticeably longer as the spring equinox arrives and the sun sets further north on the horizon. Vespers glow beyond the twilight skies in the immensity of space where comets fall and suns explode. God know what other amazing settings exist within the zones of warmth of other suns, in ours and other galaxies, but if what we can see from here is any indication, then they must be beyond extraordinary. We often wonder what types of mysterious creatures live elsewhere in space, yet if we step back for a moment and remember that we inhabit a planet floating around a sun in the vastness of the universe, then we’d realize that we need not look further than Earth and its incredible past to view life in space. We live on the most glorious and bountiful planet that we will ever know, and it is an absolute miracle that we are here. There are a finite number of seasons we’ll live through and be able to appreciate the whales and salmon and butterflies. There will come a time when you and I will no longer hear a chorus of frogs or a symphony of crickets in the spring and summer nights, or the swoosh of owls or honking geese as they fly overhead. As the grey whales move north through the swells at night beneath full moons and starry skies, they emerge from the fathoms to breech and breathe. One can only imagine what they must think of us and the great and often destructive changes we’ve exacted upon the shores and in the seas. They too have a limited number of seasons on Earth, and possess an equal right to enjoy them. Perhaps the mother whales look to their young calves whom they have just reared, then look warily at the lights of the structures on the shore, the headlights of the cars on the road, the planes in the sky, the ships on the water. Perhaps they look at us and wonder why we are always there, and they sense a fearful connection between our presence and the decimation of their habitat. Perhaps they can somehow sense that our species has a predilection for murdering them and that only a little over a century ago did we pushed them to the brink of extinction. Maybe they know what is at stake and as they look to us onshore they sing to us: don’t screw this up. Then they dive into the dark water and push on.

Aaron |

Aaron |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |